Standard Patterns in Choice-Based Games

Author: Sam Kabo Ashwell

When I was analysing the structures of CYOA works a few years back, I began to recognise some strong recurring design patterns. I came up with some home-brewed terminology, but didn’t ever lay it out in a nice clear way. This is a non-exhaustive look at some of the more common approaches, somewhat-updated (a lot has changed since then).

I should stress that these aren’t discrete categories: while a lot of works will fall very straightforwardly into a single pattern, many will involve elements of multiple patterns. (And yes, I’m aware that you can often simulate one using the mechanics of another. That’s mostly beside the point.) Also, the example diagrams I’m using are smaller and simpler than would be likely in actual works.

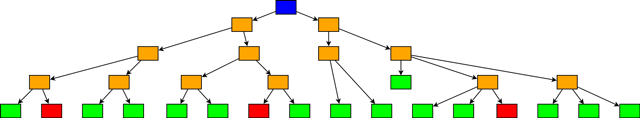

Time Cave

A heavily-branching sequence. All choices are of roughly equal significance; there is little or no re-merging, and therefore no need for state-tracking. There are many, many endings.

Effects: The time cave is the oldest and most obvious CYOA structure. It is often good for narratives about freedom and open possibility, adventures that could go anywhere, flights of fancy. Time caves tend to have relatively short playthroughs, but strongly encourage replay: they are broad rather than long. Even with multiple playthroughs, most players will probably miss a good deal of the content.

The time cave’s structure is both organised by chronological progression and detached from it. It’s ungrounded by regularity: possibility is so open that it often becomes fantastic or surreal, with different branches occupying wholly different realities. The player has velocity but little grasp, vast freedom but little ability to comprehend it.

Examples: Edward Packard’s earlier work (The Cave of Time, Sugarcane Island), Emily Short’s A dark and stormy entry; Pretty Little Mistakes.

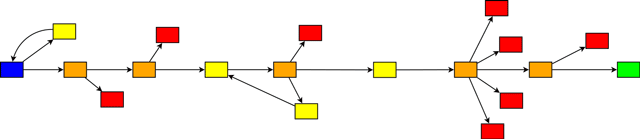

Gauntlet

Long rather than broad, gauntlets have a relatively linear central thread, pruned by branches which end in death, backtracking, or quick rejoining. The Gauntlet generally tells one anointed story, which can be adorned with optional content or prematurely ended with failure; if there are multiple endings, they’re likely to derive from a Final Choice. Gauntlets rarely rely on state to any great extent (if they do, they are likely to evolve into a branch-and-bottleneck structure.)

Effects: The player is likely to realise that they are on a constrained path, but the presentation of side-branches matters a great deal – do they mean death? incorrect answers? travel back in time? blocked paths, footnotes, or scenic details? Most often, the gauntlet creates an atmosphere of a hazardous, difficult or constrained world. Sometimes this can be punishing or depressing; sometimes it can be darkly comic; sometimes it’s a sign that you’re in a work heavily dependent on reflective or rhetorical choice. Perhaps the easiest structure to author, gauntlets can be conceived of in similar terms to linear stories, and ensure that most players will see most of the important content.

There are two major varieties of gauntlet: deadly and friendly. Deadly gauntlets mostly prune the tree with failure; friendly ones mostly do so with short-range rejoining, and look a bit more like simple branch-and-bottleneck structures. Friendly gauntlets have been vastly more common in recent years, making up a high proportion of Twine works.

Examples: Zork: The Forces of Krill. Our Boys In Uniform.

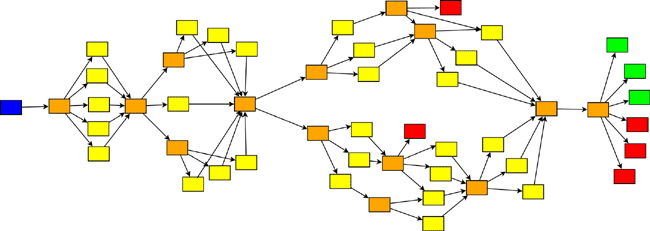

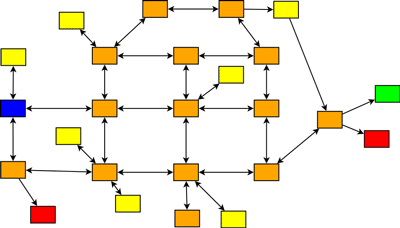

Branch and Bottleneck

The game branches, but the branches regularly rejoin, usually around events that are common to all versions of the story. To avoid obliterating the effect of past choices, branch-and-bottleneck structures almost always rely on heavy use of state-tracking (if a game doesn’t do this, chances are you are dealing with a gauntlet).

Somewhat rarely, the bottlenecks may be invisible – the plot branches and never reaches an explicit rejoining node, but the choices at the end of each branch are the same or similar, creating an exquisite-corpse effect.

Effects: Branch-and-bottleneck games tend to be heavily governed by the passage of time, while still allowing the player fairly strong grasp. The branch-and-bottleneck structure is most often used to reflect the growth of the player-character: it allows the player to construct a somewhat-distinctive story and/or personality, while still allowing for a manageable plot. There’s a tendency – not a necessary one, by any means – for playthroughs to be very similar in the early game, then diverge as the effects of earlier choices accumulate. In order for the approach to work, it has to be used in a fairly large piece; you need time to accumulate change before producing results that reflect it.

Examples: This is pretty much how Long Live the Queen works, and is the guiding principle of Choice of Games (Dan Fabulich uses the term delayed branching). It’s also a common plot structure in non-IF games that allow significant plot choices.

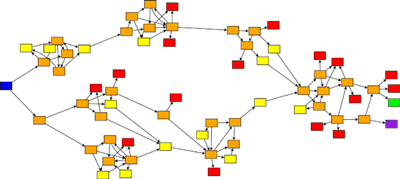

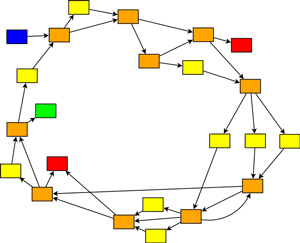

Quest

The quest structure forms distinct branches, though they tend to rejoin to reach a relatively small number of winning endings (often only one). The elements of these branches have a modular structure: small, tightly-grouped clusters of nodes allowing many ways to approach a single situation, with lots of interconnection within each cluster and relatively little outside it. Re-merging is fairly common; backtracking rather less so. Quests generally involve some level of state-tracking, and do poorly when they don’t. The minimal size for a quest is relatively large, and this category includes some of the largest CYOAs.

Effects: This mode is well-suited for journeys of exploration, focused on setting; the quest’s structure tends to be organised by geography rather than time. Indeed, most works of this kind involve a journey with a specific purpose in mind. Quests work well for grounded, consistent worlds, but within that context the player-character’s situation is constantly changing. The narrative tends to be fragmentary or episodic, like old-school D&D encounters: little chunks of story which might not have any great significance for the big picture.

Examples: The Fighting Fantasy books and their descendants (Lone Wolf, 80 Days).

Open Map

Even though quests are structured by geography, time still plays an important part: there’s a built-in direction of travel. But take a CYOA structure, make travel between the major nodes reversible, and you have a static geography, a world in which the player can toodle about indefinitely. Often this is a literal geography and relies on extensive state-tracking both explicit and secret for narrative progress. But it’s not an uncommon mode for things with assumptions grounded in the hypertext-novel idiom – static but non-linear works like Le Reprobateur.

Effects: This is often used as an imitation of the default style of parser IF, although some may be parallel derivation from the former’s D&D roots. As with classic map-based parser games, the narrative tends to become slower-paced and less directed; the player has more leisure to explore and grasp the world, but spends less of their time advancing the story.

Examples: Duelmaster; Chemistry and Physics.

Sorting Hat

The early game branches heavily and rejoins heavily (branch-and-bottleneck is a likely model here), ultimately determining which major branch the player gets assigned to. These major branches are typically quite linear – sometimes they look like gauntlets, but they might be choiceless straight-shots. Sorting Hats almost always rely substantially on state-tracking in the early game, and often bottleneck at the decision point.

Effects: The Sorting Hat is a compromise between the breadth of more open formats and the depth of linear ones. Sometimes the nature of the various branches is signaled to the player; this is kind of important, in fact, because the player is pretty likely to notice the linearity of the second half and might assume that all of their choices will ultimately get funneled into that particular thread. The player gets a lot of influence over how the story goes; however, the author may end up effectively having to write several different games.

Examples: Katawa Shoujo; Magical Makeover.

Floating Modules

A mode only really possible in computer-based works. There is no tree – or, while there may be scattered twigs and branches, there’s no trunk. No central plot, no through-line: modular encounters become available to the player based largely on state, or perhaps randomly.

Effects: This is a challenging style to write for, both because it’s difficult to intuitively grasp – writers tend to rebound quickly to a more unified structure – and because few assumptions can ever be made about prior events. Without a large amount of content, the method tends to collapse into a linear system. Because play mechanics are largely about altering stats in order to negotiate a world, there’s a strong incentive to expose those stats to the player; repeated events chosen only to affect a stat (grinding) may be a feature.

Examples: Pure examples of modular design are relatively rare. King of Chicago (hat-tip Sean Barrett) is an early example. StoryNexus and its conceptual relatives (e.g. Bee) inhabit this space, though they generally impose some more linear-progression structure on it. (Alexis Kennedy uses the term quality-based narrative to describe the general approach: ‘pieces of story like mosaic tiles, not pipes or complex machinery.’)

Loop and Grow.

The game has a central thread of some kind, which loops around, over and over, to the same point: but thanks to state-tracking, each time around new options may be unlocked and others closed off. This is a very general pattern, and can co-exist with many others. Trapped in Time, for instance, is basically a cycle-and-growing Gauntlet; Bee tames its floating-module nature with a year-long loop structure.

Effects: Loop and Grow emphasizes the regularity of the world while retaining narrative momentum. A justification is needed for why whole sections of narrative can repeat: the player-character is often following routine activities in a familiar space, engaged in time-travel, or performing tasks at a certain level of abstraction. This regularity often comes at the price of openness: many stories with a strong Loop and Grow structure involve a struggle against confinement or stagnation.

An important variation of loop-and-grow structures is spoke and hub: the game has several major branches, but they all originate at and return to a central node or set of nodes. The player may go out along each spoke once, or many times.

Examples: Bee, Trapped in Time, Solarium.